The 10 most-difficult-to-pronounce names of the Tour de France

We’ve all been there: Watching a race on TV, the breakaway or a group that got away in the final are shown, and graphics with the riders’ names are superimposed on the screen. As our eyes scan the list, we do a double take: How are you supposed to pronounce THAT? Sometimes, even the commentators can be heard to take a deep breath, or they try to avoid saying a certain rider’s name if possible. But fear not, our linguistic expert Lukas Knöfler is here to help. For years, his saiklist.help project has helped the cycling community with difficult pronunciations, and he has curated a list of the 10 hardest names in the 2025 Tour de France peloton.

Explanatory note: We’re using ⟨x⟩ to signify letters as they’re normally written, /x/ for the pronunciation according to the IPA, and [x] for very detailed pronunciation, distinguishing between small differences. ‘x’ is used for linguistic terms, “x” is used for pronunciation (near)-equivalents in other languages, mainly English.

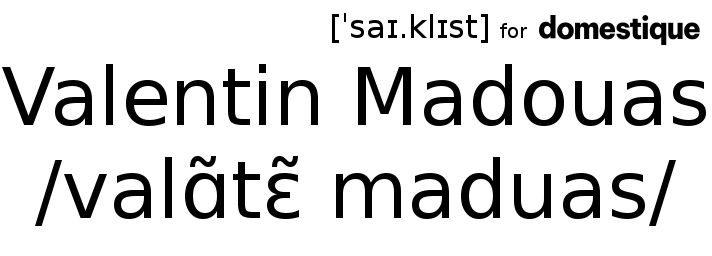

Valentin Madouas (Groupama-FDJ)

As a French name should, Madouas’ given name Valentin involves nasal sounds: / ɑ̃/ for ⟨en⟩ and /ɛ̃/ for ⟨in⟩. The surname Madouas is quite straightforward, but remember that, unlike in many other French words, the ⟨-s⟩ is NOT silent! That’s because the name is Breton in origin. Other examples from cycling where the final S is pronounced are Anthony Turgis, Matîs Louvel, Juliette Labous, or indeed the team Cofidis.

Valentin Madouas is pronounced /valɑ̃tɛ̃ maduas/. Listen and repeat!

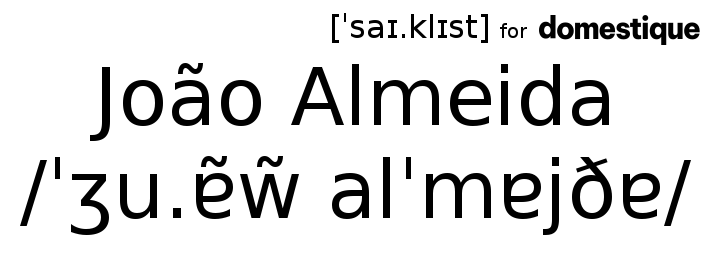

João Almeida (UAE Team Emirates-XRG)

Portuguese, like French, has nasal vowels, and the given name João is a perfect example for that. The first syllable is stressed, and the ⟨o⟩ is pronounced /u/, but the ⟨ão⟩ becomes a nasal /ɐ̃w̃/. In the surname, the stress is on the second syllable ⟨mei⟩, but with the first ⟨a⟩ is pronounced like a normal /a/, both the ⟨e⟩ and the final ⟨a⟩ are a ‘near-open central vowel /ɐ/. The ⟨d⟩ between the vowels undergoes ‘lenition’, becoming a /ð/, like the ⟨th⟩ in English “the”.

João Almeida is pronounced /ˈʒwɐ̃w̃ alˈmɐjðɐ/. Listen and repeat!

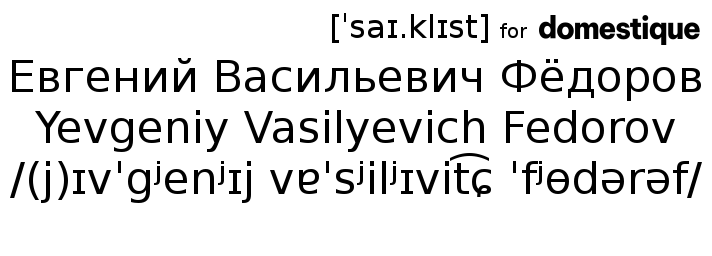

Yevgeniy Vasilyevich Fedorov (XDS-Astana)

Fedorov is from Kazakhstan, but his name is Russian, written Евгений Васильевич Фёдоров in the Cyrillic alphabet. Transcription or transliteration to the Latin alphabet isn’t standardised across countries and languages; e.g. Евгений can be Yevgeniy, Evgeniy, Yevgeny, or Evgeny. Фёдоров is most often transcribed Fedorov, but a more correct way would be Fyodorov or Fëdorov. And then there’s the patronymic Васильевич – it means “son of Vasiliy” which in scientific transliteration would be Vasil’evič but is Vasilyevich in every-day use.

In Russian, many consonants get softened, adding a /ʲ/ sound after them – similar to the /ɲ/ from Skujiņš, but less pronounced. The ⟨ч⟩ is pronounced /t͡ɕ/, similar to the ⟨ch⟩ in English “catch”, but not exactly the same. The ⟨ё⟩ is pronounced /ʲɵ/, close to the first syllable in English “yoghurt”. The stress is put on the second syllable in Евгений and Васильевич, but on the first syllable in Фёдоров.

All in all, Евгений Васильевич Фёдоров is pronounced /(j)ɪvˈɡʲenʲɪj vɐˈsʲilʲɪvit͡ɕ ˈfʲɵdərəf/. Listen and repeat!

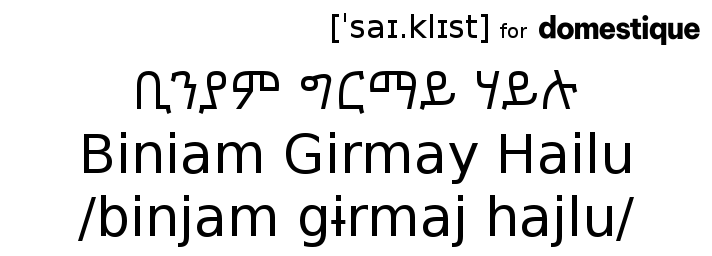

Biniam Girmay Hailu (Intermarché-Wanty)

Last year’s winner of the green jersey hails from Eritrea, and that country’s main language, Tigrinya, is written in the Ge’ez script. The Ge’ez script is an abugida, not an alphabet, meaning that every symbol denotes a consonant and optionally a vowel. Looking at each symbol in ቢንያም ግርማይ ሃይሉ, it can be transcribed Bi-n-ya-m G-r-ma-y Ha-y-lu in the Latin alphabet. But there is even less standardisation in the transcription of Ge’ez than in that of the Cyrillic alphabet, so ግርማይ has variously been transcribed as Girmay, Grmay (like the Ethiopian rider Tsgabu Grmay), Grmaye or even Ghirmay.

The latter is due to Eritrea’s heritage as an Italian colony – the Italians introduced the Eritreans to cycling, but ⟨gi⟩ would be pronounced /d͡ʒi/ in Italian, not /gi/, so they added an ⟨h⟩ to make it conform to Italian pronunciation rules. You may have noticed that the first syllable of ግርማይ, G-r-ma-y doesn’t appear to have a vowel. Since pronouncing syllables without vowels is possible but very hard, an /ɨ/ gets inserted, pronounced very similar to the ⟨ı⟩ in Turkish.

Last but not least, you should know that Eritreans and Ethiopians don’t have family names. Instead, they use patronymics (like Russian, see above, or Icelandic), but unlike those two languages, they simply add the name of their father (and grandfather) to their own given name. Biniam Girmay Hailu is “Biniam (the son of) Girmay (the son of) Hailu). So calling him Biniam, or just Bini, is not only totally fine, it’s accurate!

ቢንያም ግርማይ ሃይሉ is pronounced /binjam gɨrmaj hajlu/. ቢንያም ግርማይ is pronounced /binjam gɨrmaj/. ቢንያም is pronounced /binjam/. Bini is pronounced /bini/. Listen and repeat!

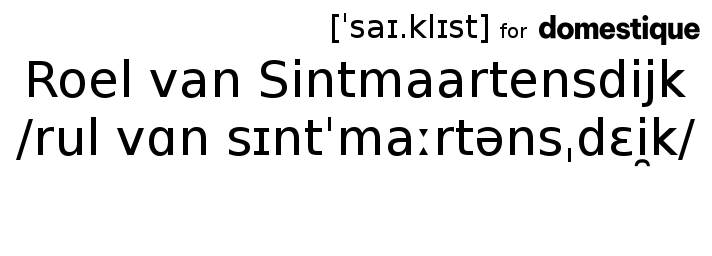

Roel van Sintmaartensdijk (Intermarché-Wanty)

One of Bini’s domestiques, Roel van Sintmaartensdijk is a name to make commentators not from Belgium or the Netherlands doubt their career choice. But Dutch is a relatively regular language when it comes to pronunciation, it’s not that complicated if you break it down.

The letter combination ⟨oe⟩ in ⟨Roel⟩ simply stands for the /u/ sound. The ⟨v⟩ in ⟨van⟩ is pronounced /v/ somewhere between the English “van” and “fan”, closer to “van”. However, the ⟨a⟩ in ⟨van⟩ is an /ɑ/, nothing like the ⟨a⟩ in the English “van” but more like the ⟨a⟩ in English “palm” (but much shorter, as “palm” has a long /ɑː/).

The surname Sintmaartensdijk consists of four elements: ⟨Sint⟩, ⟨Maarten⟩, ⟨dijk⟩, and an extra ⟨s⟩ to signify the genitive, or possessive case.

Sint Maarten is the Dutch name of Saint Martin, and dijk is Dutch for, well, a dyke (UK spelling) or dike (US spelling), the earthwork built to keep water out of low-lying lands – in other words, the very thing without which much of the Netherlands wouldn’t exist. So this translates to “dyke of Saint Martin”. Sint is pronounced /sɪnt/ with the ‘checked vowel’ /ɪ/ since it is a ‘closed syllable’ ending in consonants as opposed to an ‘open syllable’ ending in a vowel. Maarten is pronounced /ˈmaːrtən/, with a long ‘free vowel’ /aː/ in the first syllable and a ‘schwa’ /ə/ in the second syllable. In English, the final sound in “comma” is a ‘schwa’. Dijk is pronounced /dɛi̯k/ with the diphthong ⟨ij⟩ very close to British English “bait”.

Putting all this together, Roel van Sintmaartensdijk is pronounced /rul vɑn sɪntˈmaːrtənsˌdɛi̯k/. Listen and repeat!

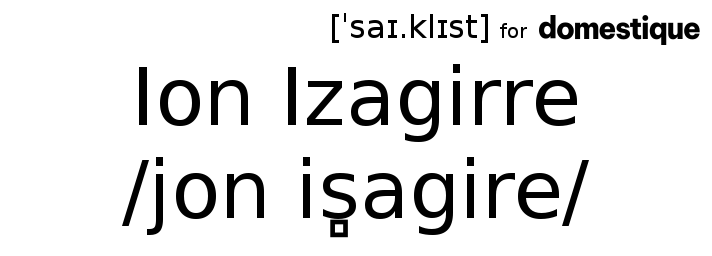

Ion Izagirre (Cofidis)

This name isn’t actually that hard to pronounce! I’ve included Ion Izagirre as an example of the Basque language in order to show the differences and similarities between Basque and Castilian Spanish.

The two languages are very similar in how they treat the ⟨r⟩/⟨rr⟩. A single R is used for what linguists call an ‘alveolar tap’. In the IPA (that’s International Phonetic Alphabet, not India Pale Ale), it’s represented by the symbol /ɾ/. An equivalent would be the ⟨t⟩ in American English “atom”. In Izagirre’s case, though, we have the ⟨rr⟩, signifying an ‘alveolar trill’ /r/ or rolled R that we all know from Spanish.

However, Basque uses ⟨z⟩/⟨s⟩ quite differently from Spanish (and many other languages, for that matter). In Iberian Spanish, ⟨z⟩ is pronounced as a /θ/, the ⟨th⟩ in English “thin”, “thanks” etc., while ⟨s⟩ is, well, a regular /s/. Basque differentiates between two S sounds, using ⟨z⟩ for the ‘laminal alveolar fricative’ [s̻], pretty much the /s/ we all know. However, ⟨s⟩ is used for the ‘apico-alveolar fricative’ [s̺] where you point the tongue towards the upper teeth instead of the lower teeth when pronouncing it, creating something that is on its way to a sibilant /ʃ/.

Finally, the ⟨g⟩ in Izagirre doesn’t undergo ‘lenition’ to a /ɣ/ as it would in Spanish, which is why the name is sometimes spelled “Izaguirre”.

Putting all this into use, Ion Izagirre is pronounced /jon is̻agire/. Listen and repeat!

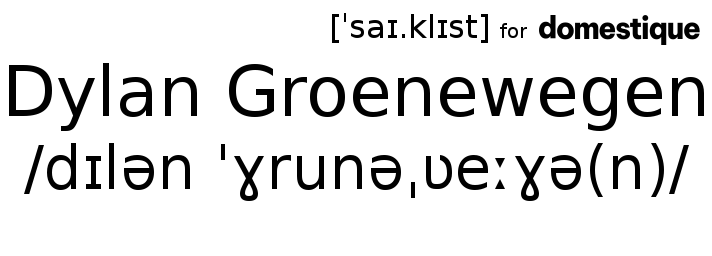

Dylan Groenewegen (Team Jayco-AlUla)

I said before that Dutch had a regular pronunciation, and it does. But when certain letters meet, that doesn’t help much when your mouth isn’t used to it. The ⟨gr⟩ is one such combination.

The given name Dylan is pronounced just like in English, /dɪlən/. The surname Groenewegen combines the rasping Dutch /ɣ/ with the rolling /r/ we already met with Ion Izagirre. The ⟨w⟩ is pronounced as a ‘voiced labiodental approximant’ /ʋ/ in Dutch; it has no direct equivalent in English but can be described as a softer /v/. The ⟨n⟩ in a word-final ⟨en⟩ is often dropped.

Dylan Groenewegen is pronounced /dɪlən ˈɣrunəˌʋeːɣə(n)/. Listen and repeat!

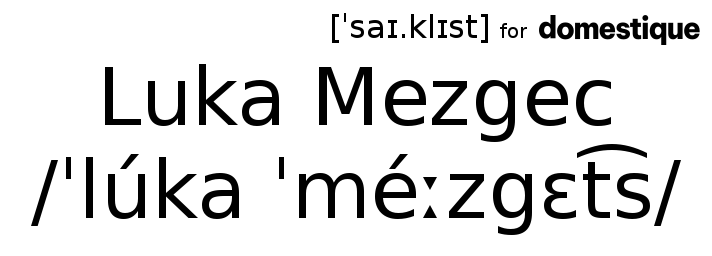

Luka Mezgec (Team Jayco-AlUla)

Another name that isn’t really that hard, but Mezgec is included as an example of a Slavic name that disproves what many people think about Slavic languages: “Every C is a CH”.

They most likely believe this because the diacritics very often get lost in English texts. That turns Matej Mohorič into Matej Mohoric, Primož Roglič into Primoz Roglic, Tadej Pogačar into Tadej Pogacar, Matúš Štoček into Matus Stocek, Lukáš Kubiš into Lukas Kubis, or Josef Černý into Josef Cerny. But in the case of Luka Mezgec (or Lidl-Trek’s Mathias Vacek), there was no diacritic to begin with! The ⟨c⟩ is simply pronounced /t͡s/.

Slovenian has rising and falling ‘tones’ on its stressed syllables, similar to many Asian languages. In Mezgec’ case, the ⟨u⟩ in his given name Luke and the first ⟨e⟩ are stressed, both have a falling tone.

Luka Mezgec is pronounced /ˈlúka ˈméːzgɛt͡s/. Listen and repeat!

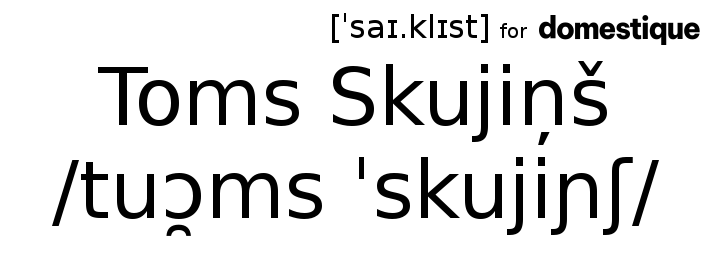

Toms Skujiņš (Lidl-Trek)

The ⟨o⟩ in the given name of the newly-crowned Latvian champion is pronounced as a diphthong /uɔ̯/. In Toms’ surname, ⟨ņ⟩ is pronounced /ɲ/, the same as the Spanish ⟨ñ⟩ or the ⟨ny⟩ in English “canyon”. To make matters more complicated, though, that is immediately followed by a ⟨š⟩, pronounced /ʃ/ like in English “shop”.

Toms Skujiņš is pronounced /tuɔ̯ms ˈskujiɲʃ/. Listen and repeat!

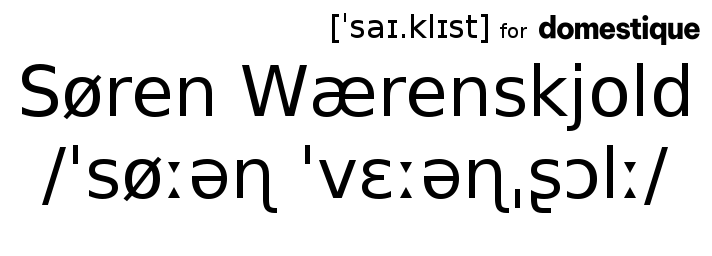

Søren Wærenskjold (Uno-X Mobility)

This name features both ⟨ø⟩ and ⟨æ⟩ as well as a number of pronunciation quirks from the Norwegian language.

Let’s start with the given name Søren: The ⟨ø⟩ is pronounced /øː/. There is no equivalent in English, but in French the vowel in the word “queue” is spot on (though the /øː/ in Søren is longer). The second syllable ⟨ren⟩ is special: While the ⟨e⟩ is a rather regular ‘schwa’ /ə/, he ⟨r⟩ and the ⟨n⟩ combine for a ‘voiced retroflex nasal’ /ɳ/.

In the given name Wærenskjold, the ⟨w⟩ is pronounced /v/, the ⟨æ⟩ is a mid-front unrounded vowel /ɛ/ like in the English “dress”, and like in the given name, ⟨ren⟩ is pronounced /əɳ/. The ⟨skj⟩ consonant cluster is pronounced as a ‘voiceless retroflex sibilant fricative’ /ʂ/, close to but not quite the same as the /ʃ/ in English “shop”. The ⟨o⟩ is pronounced /ɔ/ like the vowel in English “thought” (but not as long), and the ⟨d⟩ is silent itself, but makes the ⟨l⟩ longer.

Putting all that together, Søren Wærenskjold is pronounced /ˈsøːəɳ ˈvɛːəɳˌʂɔlː/. Listen and repeat!